I'm learning the ropes of baking in Cuba with these butternut squash cupcakes with cream cheese frosting.

Havana, Cuba -- I never enjoyed baking before I moved to Cuba. My husband and I have spent many years living in China, where home ovens are a rarity. I like to taste things as I go along. I don’t like to measure. I’m generally not into following rules when I cook — all of which sometimes translates into disaster when I bake.

But since moving to Cuba, I’ve caught the baking bug. Maybe it has to do with seeing baked goods wherever I go in Havana. Since Raul Castro began allowing Cubans to open private businesses about half a decade ago, hundreds of bakeries have appeared across the island, because it’s one of the less expensive businesses to start and sugar is a staple crop of Cuba. Maybe it’s because my daughter has a sweet tooth, one that’s even sweeter than mine. Or maybe it’s my wanting to emulate my friend R, my best friend in Havana, who happens to be one of the spunkiest, funniest, and loveliest octogenarians I’ve ever met. She also happens to make the most delicious chocolate cake I’ve ever tasted.

The story really begins with R and her chocolate cake. Like many Cubans, R has to work to supplement her measly pension of less than $40 per month (and she’s one of the luckier ones — her retirement is one of the higher ones in Cuba). Fortunately, she has a talent for baking and sells her chocolate cakes to a paladar, one of the many private restaurants that has sprung up since Raul’s reforms. She learned to make this cake when she was living in Paris, where she also coincidentally met and fell in love her husband, a Cuban revolutionary. The cake is called a decadence, and that’s the perfect word to describe it. It’s the best chocolate cake I have ever had — very dense and rich, but not overly so. It’s just the right amount of decadence. (I’m still working on her to give me the recipe.) Since I tried it, I’ve been telling everyone in Havana about this chocolate cake and urging her to sell it more widely.

In the meantime, inspired by R and struggling to find something to do with my surplus carrots and pineapples one afternoon, I tried out a recipe for carrot cake, a dessert that doesn’t exist on the island. “Carrots? In a cake?” several friends have asked me incredulously after telling them about it. After I gifted a carrot cupcake to another local friend, he began licking off the icing as if it were a lollipop.

Recently, I gave a carrot cake to my friend Angie, an American who works with my husband. Later that week, Angie was interested in buying a chocolate cake from R. R happened to be out of town. In a text message, Angie replied that she’d take my carrot cake in its place. It was the first order of a cake I’d received from anyone, and I went into a fury trying to find all the ingredients that day.

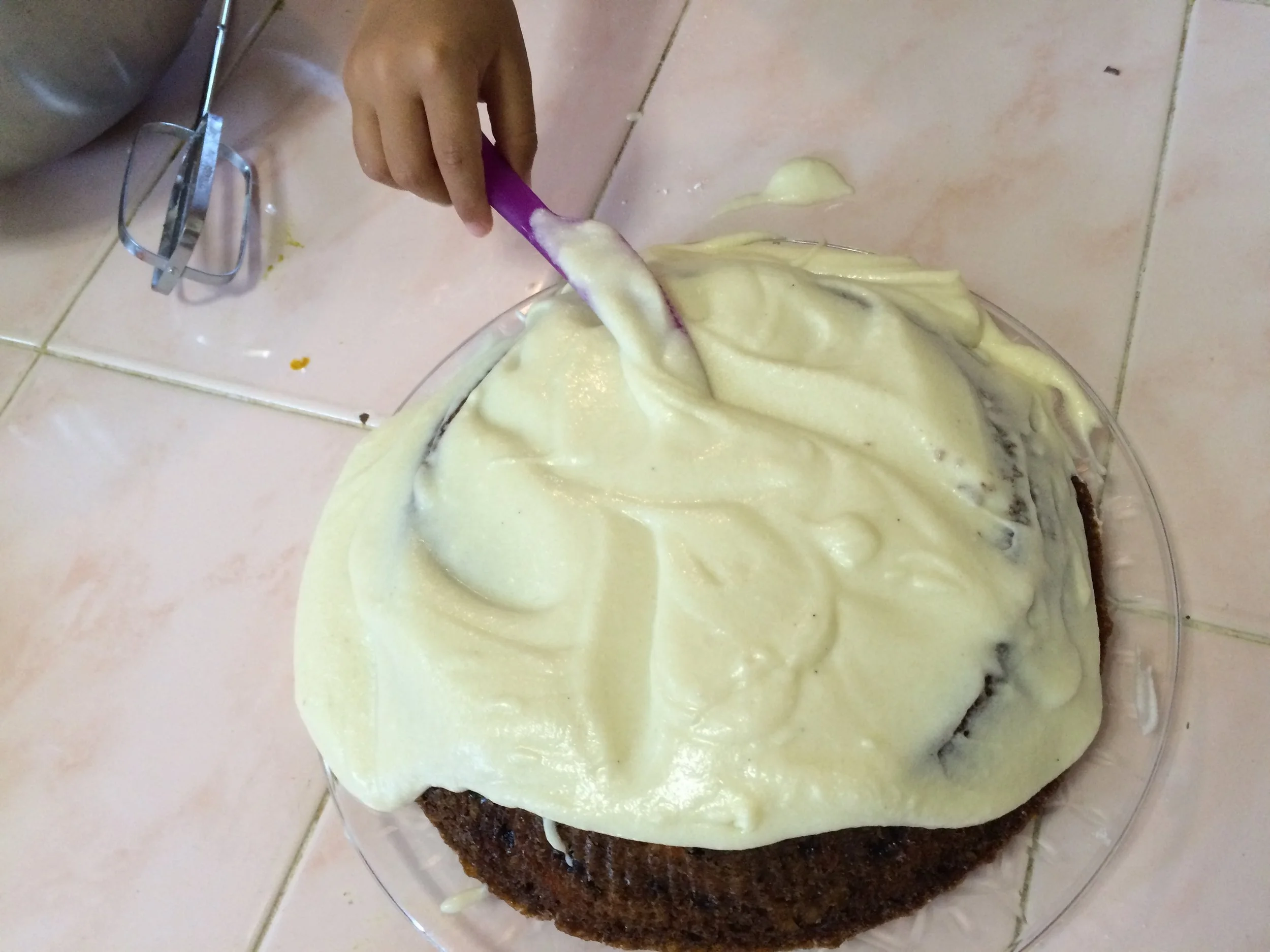

My daughter and I working on our first cake order. It wasn't exactly pretty, but it was delicious.

By the afternoon, I’d finished baking the cake and, with my daughter’s help, I’d spread on top of it a generous goopy layer of cream cheese frosting. It was far from looking like a professional cake, but I was confident that it tasted better than it looked. “Your carrot cake is ready,” I texted her. I received a call from her a few minutes later. “Whoops!” she said. She actually hadn’t meant to order a cake; she’d been planning to take the one that I’d brought her earlier that week, which she’d put in her freezer. In any case, she took the freshly-baked cake to my husband’s workplace. Everyone loved it, and I began getting more orders.

Baking on scale has helped me understand what it’s like to run a business in Cuba. It’s a challenge to maintain supplies. My housekeepers and I are always on the search for cream cheese and butter. I’ve befriended the ration-store clerk down the street, in my effort to maintain a steady egg supply. We have to grind our own sugar to make the powdered variety. I’ve localized all the ingredients for the cake except for the walnuts, which I bring in from the U.S., and the disposable pie plates in which I bake them.

Baking has also taught me some lessons. One morning at the agro (the farmers’ market), I couldn’t find a single carrot at the stalls. I went from market to market looking for the root vegetable. “Perdida,” said one of the sellers. “They’ve disappeared.” Before that, I had no idea that carrots have a season; or rather that there is a season in Cuba when carrots weren’t available. I had a couple of orders to fill and no carrots. At home, I went through my refrigerator drawers to see if I truly had no more carrots and came across another orange piece of produce — calabaza, or the Cuban version of butternut squash. My housekeeper grated it and folded it into the batter. An hour later, two golden butternut squash cakes came out of the oven. They were more moist and delicious than the original carrot cake, proving that I can actually improvise when I bake.